From Do You Want Total War?, Part Two, explaining how Sean (the narrator) started becoming interested in history:

On my eighth birthday, my parents gave me a copy of The American Heritage Picture History of World War II. Although I’ve worn out the book’s binding, to the point that pages snap away from the spine if I turn them carelessly, I still look at it from time to time. Its 610 pages of text hold up surprisingly well, but its 720 photographs were its star attraction to a young child who had never felt history come to life before. I had only ever lived in full color, and the black-and-white world of those pictures was impossibly exotic to me, even before I first noticed the Spitfire’s elegant curves and the meticulous angles of an Essex-class aircraft carrier’s flight deck. (I myself have moved on from such mechanical fetishization – I’m a “form follows function” guy when it comes to such things, and the Spitfire drawing hanging above my desk at home is a prepubescent relic – but many history geeks never do, and I can understand why.)

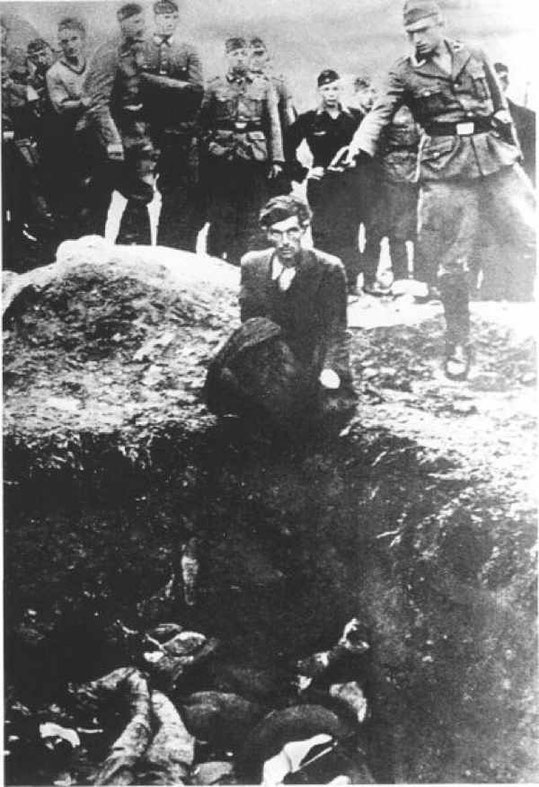

Among the book’s many images detailing the horrors of war is a picture I still can’t shake. Its central character is a gaunt figure, a man likely of Jewish origin with long, Slavic cheekbones. He stands at the precipice of an open mass grave, staring forlornly and uncomprehendingly at the camera, with dead bodies visibly stacked beneath him at the bottom of the photo. To his right is a German soldier, pointing a pistol at his head; behind him is a queue of other men and women in civilian clothes, each shepherded forward by other soldiers and waiting in turn to receive a bullet in the brain. It’s a haunting picture that asks me many questions, both metaphysical and mundane: What goes through a man’s mind, seconds before being murdered? Why would the victims simply queue for their fate like that and not offer resistance or try to escape? How could anyone impassively photograph a scene like this? When the photographer finished developing his film, how much would his sense of professional pride at the quality of his work be tainted by any understanding of what he had witnessed? How does a photographer come to be at that place at that time to take that picture? Was he the Wehrmacht’s official Chronicler of Atrocities, had he signed up as a war correspondent and made a regrettable career diversion, or would he have gladly traded his Leica for a Luger and shot the victims himself? Is a pistol really the best weapon with which to conduct mass executions? What happens to the queue of victims while the executioner loads a new ammunition clip, or when he runs out of bullets altogether and has to wait for a new supply – does everyone just shuffle their feet in embarrassment, like supermarket patrons when the checkout lady calls several times over the loudspeaker for a price check? Or do different shooters take turns, like blackjack dealers in a casino?

Many horrible photographs were taken during World War II, so one might ask why I remember this particular image so well instead of, say, a photo of stacked skeletons at Auschwitz or any other depiction of carnage or brutality. Well, one of my fourth-grade friends – a kid named Stewart, the sort of friend you have before your tastes in friends become discriminating – discovered this image while flipping through the book at my house, and he thought it was hilarious. “Look at that guy!” he exclaimed, pointing and laughing. “His face, and the gun right next to his head!”

“He’s about to get shot,” I said.

“I know!” he said.

I forced out my own nervous half-chuckle. Stewart looked at the photo again, pointed at the condemned man one last time and shook his head, then continued thumbing toward the book’s back cover.

It took me a long time to deconstruct that conversation. First, I thought Stewart was a complete idiot. Last year, I stumbled across the photo again and broke into a fast, chilling sweat: had I accidentally uncovered a psychopath? Was it my duty to inform the authorities? Now, though, I’ve come to view that exchange more sympathetically. Most fourth-graders couldn’t begin to mentally process an image like that. Stewart was looking at an odd, Eastern European face contorted by stress and despair into something virtually alien; the gun pointing at it might as well have been held by Yosemite Sam. What response to this should you expect? Besides, laughter can be a defense mechanism; if you didn’t laugh at some of these things, you’d surely cry. Stranger than Stewart’s response, I now realize, is my parents’ willingness to expose me to images like these at the age of eight. Perhaps my gaming hobby is an attempt to create order out of the chaos I’ve studied for more than half of my life to-date? That thought has crossed my mind, not that I intend to explore it too closely.